Section 11 Cyclic Groups

## Loading required package: pracmaA group \(\mathsf{G}\) is cyclic if \(\mathsf{G}= \langle g \rangle\) for some \(g \in \mathsf{G}\).

For example, \(\mathbb{Z}= \langle 1 \rangle\) is an infinite cyclic group under addition, and \(\mathbb{Z}_{n} = \{ 0, 1, 2, \ldots, n-1\} = \langle 1 \rangle\) is a cyclic group under addition mod \(n\).

Here is the Cayley table of \(\mathbb{Z}_{10}\). See Modular Arithmetic for the R function that produces these tables for any value of \(n\).

## 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

## 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

## 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0

## 2 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1

## 3 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2

## 4 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3

## 5 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4

## 6 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5

## 7 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6

## 8 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

## 9 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8Theorem. (Fundamental Theorem of Cyclic Groups) If \(\mathsf{G}= \langle g\rangle\), then

Every subgroup \(\mathsf{H}\le \mathsf{G}\) is cyclic (thus, \(\mathsf{H}= \langle g^k \rangle\)).

If \(|g| = \infty\) then \(\langle g \rangle = \{ \ldots, g^{-3}, g^{-2}, g^{-1}, 1, g, g^2, g^3, \ldots \}\) and all of these elements are distinct.

If \(|g| = n\) then \(\langle g \rangle = \{1, g, g^2, \ldots, g^{n-1} \}\) and all of these elements are distinct (thus, \(|g| = |\langle g \rangle|\)).

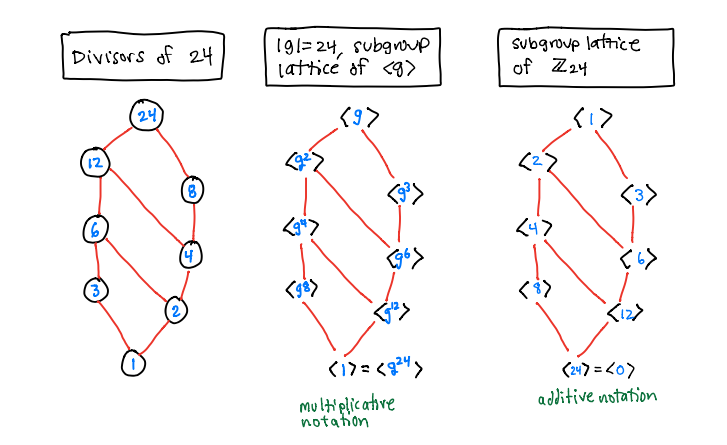

If \(|g| = n\) then the subgroups of \(\langle g \rangle\) satisfy:

\(\langle g^k \rangle = \langle g^d \rangle\), where \(d = \gcd(k,n)\).

\(|\langle g^k \rangle| = \frac{n}{d}= \frac{n}{\gcd(k,n)}\), which is a divisor of \(n\).

If \(\ell \vert n\), then \(|\langle g^{n/\ell} \rangle|\) is a subgroup of size \(\ell\) and is the only subgroup of size \(\ell\).

Note: (d) says that, in a finite cyclic group of order \(n\), there is exactly one subgroup for each divisor of \(n\) and those are all the subgroups.

Corollary If \(\mathsf{G}= \langle g \rangle\) is a finite cyclic group of order \(n\). Then \(\mathsf{G}= \langle g^k rangle\) if and only if \(\gcd(k,n) = 1\).

Thus, for example, the generators of \(\mathbb{Z}_{10}\) above are

## [1] 1 3 7 9Infinite cyclic groups:

Our favorite infinite cyclic group is the set of integers \(\mathbb{Z}\) under addition.

The subgroup \(\langle \pi \rangle \le \mathbb{R}^\ast\) is an infinite cyclic group \[ \langle \pi \rangle = \{\ldots, \pi^{-3}, \pi^{-2}, \pi^{-1}, 1, \pi, \pi^2, \pi^3, \ldots \} \le \mathbb{R}^\ast. \]

See Complex n-th roots of unity for the infinite cyclic group \(\langle 1.02 e^{2 \pi i /17} \rangle \le \mathbb{C}^\ast\).

Some finite cyclic groups:

The rotation group of an n-gon: \[ R_n = \{1, r, r^2, \ldots, r^{n-1}\} \le \mathsf{D}_n \]

Sometimes the group of units \(U(n)\) under multiplication mod \(n\) is cyclic. For example, here is a demonstration that \(U(21) = \langle 2 \rangle\). This is a cyclic group of order 18.

## [1] 1 2 4 5 7 8 10 11 13 14 16 17 19 20 22 23 25 26## [1] 1 2 4 8 16 5 10 20 13 26 25 23 19 11 22 17 7 14 1